Kohelet and Varieties of Interpretation

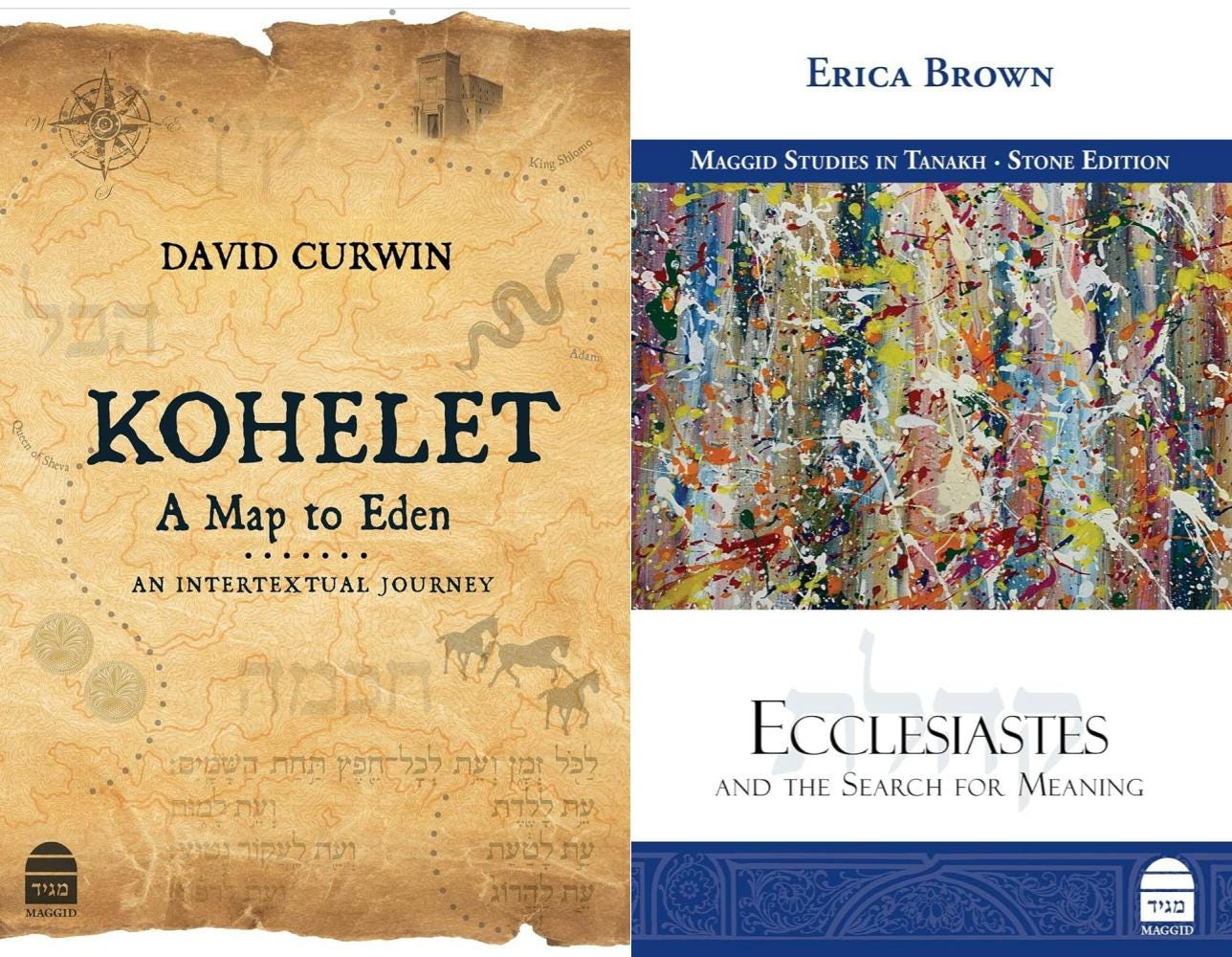

Sefer Kohelet, also known as the Book of Ecclesiastes, stands out like a sore thumb in the Hebrew Bible. It presents neither a clear narrative nor a recognizable Jewish philosophy. Yet it is not only part of our canon but read publicly in synagogue for the holiday of Sukkot. Koren’s Maggid Books recently published two works in the hope of providing readers with more understanding and appreciation of this mysterious text.

Dr. Erica Brown’s Ecclesiastes and the Search for Meaning is part of the official Magid Studies in Tanakh series, which seeks to “explore the concepts, themes, literary artistry, and historical context of individual books in the Bible.” In Dr. Brown’s case, she acknowledges that “while I cite academic research… this book emerges primarily from the study of classical Jewish scholarship, from talmudic and midrashic interpretations to medieval and pre-modern commentators. They often anticipated the same issues contemporary scholars point to but did so hundreds if not thousands of years earlier, with a different agenda: for religious edification.”

That does not mean, though, that her book is not deeply in conversation with modern academia. to the contrary, “classic commentaries often bypass the larger contextualization that illuminates the placement of verses within a chapter or the intertextuality that comes with cross-referencing… Contemporary biblical scholarship often provides this broader framework and alerts us to literary, archeological, and historical aspects that can enhance our understanding.” She notes, however, that “as a project of faith, a more scientific approach has limits.”

This leads to a seemingly insurmountable problem. If both religious commentary and academic scholarship have their weaknesses, how does one move forward to examine a text like Kohelet productively? Dr. Brown offers a fascinating response:

Some perceive these two interpretive communities - the religious and the academic - as at war with each other. For some, even opening a book of scholarship is threatening and diminishes the religious underpinnings of studying Tanakh. Any publication that calls authorship into question is highly problematic, destabilizing, and to be avoided. The very term “biblical criticism” carries the disparaging notion that the Bible is being criticized, making such an undertaking a dangerous encounter designed to topple the faithful - which it sometimes has.

For academics, religious interpretation can involve strange midrashic twists that are not taken literally. Philosophical issues are often ignored in such readings as are the problematic actions of biblical heroes. Classic Jewish Bible study is often dismissed as unsophisticated, unenlightened, and etymologically inaccurate, despite the fact that those with a solid Jewish education often have far better linguistic tools than many of those who have made their way through the Academy.

…

Studying Tanakh benefits from establishing a general, overall impression before reviewing exegetes… This allows the text to both speak and to mystify. Then it is time to identify and assemble questions, many - but not all - of which are addressed by classic exegetes, so that one can appreciate the work of these interpreters. Surveying the comments that surround the page, taking special note when they disagree with each other across continents and time, and considering what they see as the verse’s mysteries further deepens the study. When they argue with each other about meaning, the reader must be content with irreconcilable readings… Then it helps to step back again from microscopic scrutiny to gain the larger perspective of where this verse fits within its neighboring verses, the chapter, or the book itself. The classic exegetes are often little help here, as this was rarely an interest. At this stage, fortifying oneself with academic scholarship helps sustain attention and helps the reader notice details…. While, for some, such comments appear threatening and challenge the spiritual/intellectual understandings of religious interpreters, others may find they help provide a more “intense and immersive” reckoning with the words.

Dr. Brown admits that this approach of supplementing traditional understandings with scholarly ones may not work for all of her readers, but it is what works for her and so it is what she utilizes in her analyses. Because of this, in addition to traditional commentaries, she also cites “the work of contemporary philosophers, psychologists, artists, novelists, and others because Kohelet is both very ancient and strikingly modern in its themes: wisdom, mortality, work, purpose, meaning, memory, pleasure, piety, and oblivion… Additionally, at a time when major assumptions we have made about work, relationships, community, and life itself have been called into questions by global health threats, political havoc, and natural disasters, it would seem a missed opportunity not to bring Kohelet’s wisdom to bear on these tectonic shifts.”

This use of contemporary scholarship comes out most clearly in Dr Brown’s discussion of Kohelet’s authorship. Traditional commentators identify Kohelet as King Solomon (Shlomo HaMelech). But since he does not explicitly name himself, most contemporary scholars reject this idea. Taking all of this into account, Dr. Brown reaches the conclusion that

There is no conclusive evidence as to the authorship of Kohelet or its intended audience. Suppositions are made by both ancients and moderns by piecing together literary subtleties or linguistic likelihoods, political agendas or distinctive religious signals. It is easy to find oneself tangled in authorship questions that become distracting rather than edifying. Kohelet was ultimately canonized not because of its author, but because of its content. One can make the case that it was likely written by a well-known, magisterial, and authoritative hand. But, because its truth and contradictions speak so profoundly to the human condition, even and perhaps especially, anonymous authorship would not and cannot diminish its importance or its richness. Kohelet’s audience has become its readers throughout history.

This focus on content over identity is perhaps the biggest difference between Dr. Brown’s book and the other recent English volume on the subject. David Curwin’s Kohelet: A Map to Eden. Curwin takes for granted that Kohelet was written by King Solomon not only because the biographical references throughout match up, but also because there is significant value when one “reads the way a book asks to be read” and that “Kohelet asks to be read as the reflections of Shlomo.” Rather than isolating particular verses, Curwin’s approach looks at the whole of the book as King Solomon’s grand retrospective, full of references to “one person whose path most closely fully resembled his own: Adam. As the first human, Adam represents all humanity, and through his reputation, Shlomo was the first representative of Israel to be universally known. The entire world was in Adam’s dominion, and Shlomo could acquire whatever he desired; no other figure in the history of the nation had such a universal scope.” As such, “Shlomo identified with Adam’s life, and so he wrote Kohelet in a way that reflected both Adam’s life and his own. By writing as Adam, Shlomo shows that nothing has changed; the downfall of man has existed since the very beginning.”

This leads Dr. Brown and Curwin to different (yet similar) understandings of the same ideas. Take, for example, Kohelet’s use of the word hevel. Dr. Brown writes that “with so many apparencies of the word in just twelve chapters, it’s likely that the concept of Hevel is not confined to one meaning… there are different nuances and possible progression throughout the book.” Vanity, vapor, breath, futility, mortality, and transience are all offered by various scholars. Dr. Brown, however, goes with the definition of temporality:

Where transience is defined as something that does not last for a long time and can apply to anything from perishable food items to those who move from place to place, temporality is specifically related to an understanding of the way time functions. Humans and all living things are bound by temporality. Kohelet begins his search for enduring truths about life and meaning. Yet he discovers that, despite his mental investment in the quest, everything breaks down, disappears, and changes. Time marches on but little of the known universe marches on with it. Humans die. Beauty deteriorates, just like vanitas paintings depict. Magnificent buildings outlive their use and then slowly collapse. the natural world works in cycles and those cycles continue whether or not humans are there to bear witness. In the beginning, the weight of temporality is crushing and frustrating for Kohelet - as if he is asking: “Is there any point in living now if I will not live forever?” Over time, Kohelet recognizes that it is precisely temporality that offers humans beauty, meaning, and joy.

Curwin, on the other hand, reads the word hevel as a reference to Adam’s son of the same name. In that context, the word was clearly identified with “breath:”

Breath itself can be viewed as miraculous. Like the initial miracle of God breathing life into Adam, Kohelet notes the wondrous nature of babies being able to breathe… Hevel continued to surprise everyone and defy the odds by being a rebel, a shephard. He was full of breath, full of life. After his murder, however, his name took on a much more sinister meaning. It still meant “breath,” but once that breath was gone, it showed just how pointless life and breath really are. Justy because you are breathing one moment doesn’t mean you’ll be breathing the next… Adam had no power over the life-breath; he could not save Hevel on the day of death.

This way of understanding Kohelet “enhances our understandings of both stories… the Adam story helps us understand what Shlomo was experiencing at the end of his life: pain and regret. Likewise, the book of Kohelet helps us understand the Adam story by showing us how responsible Adam felt for the death of Hevel.” These references are important for King Solomon to make because “Just as Adam bemoaned the disputes between his children that eventually led to violence, Shlomo might have foreseen and dreaded the upcoming split of his kingdom, eventual civil war, and disagreement over the way to sacrifice (which was the root of the dispute between Kayin and Hevel as well). According to our understanding of Kohelet, Adam felt responsible for Hevel’s death. Shlomo, too, bore guilt over what happened to his descendants.”

While both Dr. Brown and Curwin understand Kohelet as making a profound point about mortality, Dr. Brown understands the point as being philosophical while Curwin sees it as autobiographical. In both cases, new food for thought is uncovered for readers to chew on and the depth of this remarkable biblical book is uncovered. Either (or both!) of these books will provide much to think about as we utilize Sukkot’s “time of our happiness” to come face to face with our biggest questions. Dr. Brown writes that we do this because

the transitory nature of human life is, for Kohelet, the reason for both crushing pain and soaring joy… The cycles of time, the ways of nature, and the movement from on regeneration to another offer tedium and sameness but also solace and relief. Whatever our anxieties, they, too, will cycle into other positive feelings because we do not live lives of stasis. We do not end out High Holiday season with Yom Kippur. We conclude it with Sukkot. We conclude it with Kohelet. Joy, we are reminded on Sukkot and throughout all of Kohelet, is a choice.

Or, in Curwin’s words, “at the end of his life, Shlomo understood that the futility of life can overwhelm a human being when their relationship with God is shattered… The temporality of life could not be averted by building houses of stone. Ultimately, there is no difference between a temporary booth in the wilderness and a majestic palace in the capital. To grasp eternity, one must connect with the Eternal. That is the message of Kohelet, and it is also the message of Sukkot.”

Both books are available at korenpub.com. Chag Sameach!

Please review Shmuel Phillip's Talmud Reclaimed next. It's incredibly good and shockingly geared to a chareidi audience with a chareidi publisher.