On Being a Rabbi

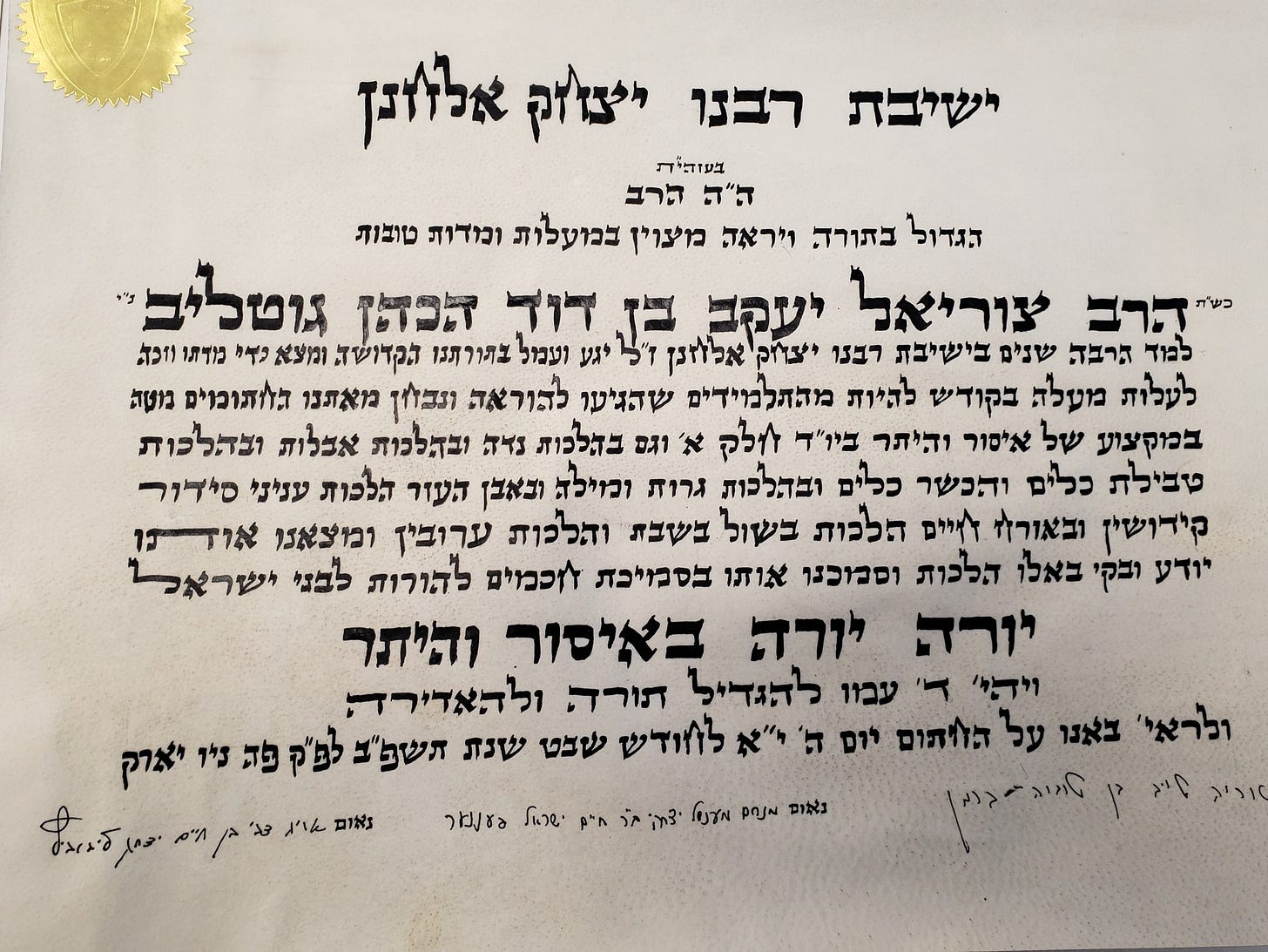

Right now, I’m in what I like to call “limbo period.” The brunt of my work in Ottawa has wrapped up, but we have yet to relocate to Philadelphia. This gave me a rare opportunity that I couldn’t help but take advantage of. A friend of mine hosted a kosher wine-tasting program for Jewish Ottawans in their 20s and 30s. Since I would no longer be hosting my own events in the city for this demographic, I was able to go not as “Rabbi Steven Gotlib” but just as “Steve Gotlib” - another 28 year-old Jew in Ottawa. I dressed relatively casually and planned to use the evening as a brief reprieve from the chaos of so many life transitions happening at once. Conversation took an interesting, though predictable, turn when someone who didn’t know me asked what I did. I was tempted to just say “I work in marketing,” but one of my regular participants swooped in and said something along the lines of “you don’t know Rabbi Gotlib?” This, of course, led to the reaction of “Oh, you’re a rabbi?” I responded that “that’s what my ordination certificate says” and after some laughs the conversation transitioned to exclusively Jewish topics.

The tension between being a young professional while also being a rabbinic figure has always been a strong one for me but attending that program as a participant rather than as a rabbi allowed me to reflect on just what being a rabbi means to me. I decided that it was appropriate to reflect on that today given that it’s the Chag HaSemikhah at Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary - an event celebrating the ordination of 150 Modern Orthodox rabbis who completed their studies at RIETS within the past few years (myself included). The Chag can be livestreamed here, and I highly recommend tuning in today at 1:00pm.

If you asked me since I was 10 years old what I wanted to be when I grew up, “rabbi” would have been in the top three. It so naturally combined everything I ever wanted to do. In many ways, it’s like being a teacher, psychologist, businessman, and laywer all in one package. In the 90s, RIETS put out a volume edited by Rabbi Basil Herring entitled The Rabbinate as Calling and Vocation. It contains 24 valuable essays about what the rabbinic profession may look like, each written by an expert in that style. Rather than sharing an excerpt, the Table of Contents says a lot:

The Rabbi as Halakhic Authority, Rabbi Hershel Billet

The Rabbi as Teacher, Rabbi A. Mark Levin

The Rabbi as Outreach Practitioner, Rabbi Ephraim Buchwald

The Rabbi as Proponent of the New Torah Life-Style, Rabbi David Stavsky

The Rabbi as Administrator, Rabbi Mordecai E. Zeitz

The Rabbi as Caregiver, Rabbi Israel Kestenbaum

The Rabbi as Counselor, Rabbi Joel Tessler

The Rabbi as Guide - At the Chuppah and Graveside, Rabbi Hashkel Lookstein

The Rabbi as Preacher and Public Speaker, Rabbi Abner Weiss

The Rabbi as Leader of Prayer Services, Rabbi Charles D. Lipshitz

The Rabbi as Community Relations Professional, Rabbi William Cohen

The Rabbi as Political Activist, Rabbi Louis Bernstein

The Rabbi as Resource for Youth, Rabbi Elan Adler

The Rabbi as a Personality, Rabbi Reuven P. Bulka

The Rabbi as a Ben Torah, Rabbi Mordechai Willig

The Rabbi as a Judaica Scholar, Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

The Rabbi as a Unifying Force, Rabbi Saul Berman

The Rabbinate as Family, Dr. Irving N. Levitz

The Rabbi as Public and Private Individual, Rabbi Basil Herring

The Rabbi as Wage-Earner, Rabbi William Herskowitz

The Rabbi as Policy Maker, Rabbi Immanuel Jakobovits

The Rabbi as Contemporary Leader, Rabbi Robert S. Hirt

The Rabbi as Spokesman for Modern Orthodox Philosophy, Rabbi Shubert Spero

The Rabbi as Spiritual Leader, Rabbi Norman Lamm

While each of these chapters represents a specific specialty, it is becoming an increasingly common expectation for contemporary rabbis to embody all of these in one way or another. See this excerpt, for example, from Stephen Fried’s book, The New Rabbi:

“Congregations all want to hire the same rabbi,” I was told. “They all want someone who attends every meeting and is at his desk working until midnight, someone who is 28 years old but has preached for 30 years, someone who has a burning desire to work with teenagers but spends all his time with senior citizens, basically someone who does everything well and will stay with the congregation forever.”

The aspect I want to focus most heavily on in this essay is the chapter entitled “The Rabbinate as Family.” When I first read it, I assumed it meant what we were often told in rabbinical school - that it’s hard for rabbis to have friends outside of those we grew up with and our fellow rabbis. However, a more accurate title for this chapter may have been “The Impact of the Rabbinate on Family.” It is, in fact, a study investigating the lives of rabbinic spouses and children. In it, Dr. Levitz concludes as follows:

Where interpersonal relationships are confounded by projections and expectations related to their being children of rabbis, their developing identity and emerging selfhood tend to be tempered by ambivalence and conflict. The very special status afforded them as extensions of their father’s clerical position excludes them from full acceptance among peers. Isolation frequently becomes the price paid for noblesse oblige.

The community, always a significant factor in rabbinic life, tends to affect children of rabbis in several ways. The greater the turbulence, factionalism, and instability a community exhibits, the more stress, anxiety, and insecurity the rabbinic family will experience. Disillusionment with yesterday’s supporters who have become today’s detractors tends to make many rabbinic children less trustful of allegiances and more wary of relationships within the community. Never too far from consciousness is the realization that the rabbi serves at the pleasure of his congregation, and that job security, financial stability, and a sense of personal well being are contingent upon the good will of the congregation. Children of rabbis grow up in the every-present shadow of this reality.

Several significant implications have emerged from this analysis. For the rabbi’s child, self-esteem is enhanced with the experience of feeling valued as an integral part of the family group in its designated work with the congregation. in positively regarding the function prescribed to the rabbi’s child by the family, the role itself takes on greater value. Secondly, if the source of stress is perceived by the rabbi’s child as emanating from the congregation and not as a veiled rejection by the rabbinic father, emotional support tends to develop within the family.

Third, the ability of rabbinic parents to separate work from family life creates “community-proof” boundaries. Divesting themselves of the trappings of the rabbinic role appears crucial to development of normal life with all the needed support it has to offer.

Finally, there is a reaffirmation of the importance of the rabbi’s role as husband. Where the marital relationship is strong, the positive effects are felt throughout the family system.

It is interesting to note that the majority of the respondents in this study were either students preparing for a professional career, or individuals professionally engaged in some form of community service. There is an intriguing possibility that children of rabbis who grew up with the ideals of public service, albeit with the insecurity of dependence on a congregation, have chosen careers or advocations that permit for the fulfillment of the service ideal without the insecurity of dependence on others. In a sense, most of the children of rabbis in this study chose to become secular clergy, independent of congregations, but in the service of others nonetheless.

This study, in its attempt to examine the impact of rabbinic life on children of rabbis, has implications not only for rabbinic families, but for all families where stress, vulnerability, and insecurity exist as a factor of daily life. It underscores the importance of family boundaries that protect a family from outside intrusion while permitting it to develop supportive cohesion from within. It reconfirms the long known observation regarding the centrality of the marital dyad and its ability to either buffer children from external stress or itself become a source of stress.

This, in effect, presents a picture of what many call "rabbi’s child syndrome.” One poignant anecdote in the study is the “not uncommon” experience of a particular rabbi’s daughter, who

had seriously dated the son of a congregant only to terminate the relationship when she came to realize that her being the rabbi’s daughter was for him one of her most attractive attributes. “I suddenly felt as if I were only an extension of my father’s profession, and stripped of my own selfhood.” She never dated in the community again.

What all of this goes to show is the importance of a lesson emphasized by my teacher, Rabbi Dr. JJ Schachter, time and again: NEVER SACRIFICE YOUR FAMILY.

Being a rabbi means a great deal to me - it’s the only professional where I can fully be myself and play to every one of my strengths. It allows me to learn and share Torah while being with so many incredible people at important times in their life. It is the best job in the world. At the same time, it’s a profession that comes with many profound challenges and impacts not only myself (who despite being a young professional, often feels neither young nor professional around my secular peers) but my family as well. I hope that in sharing some of this, rabbis and community members can work together to create healthy communities and environments where we and our children can all live our best and most fulfilled lives together. And I am so excited to be moving to a community where that seems to not only be possible but expected.