The last entry in this series explored Rabbi Dr. Neil Gillman’s formulation of the Conservative Movement’s origins. Essentially,

The Conservative Movement is a direct carry-over from Zacharias Frankel’s positive historical school of thought; and

Like Frankel’s school, the Conservative Movement broke-away from Reform, but shared many Reform assumptions about Halakhah from the beginning.

This telling is not unique to Gillman. The vast majority of “Intro to Modern Judaism” university classes teach something similar.

Indeed, the above model explains a lot about the state of Conservative Halakhah. If the Movement is effectively Reform, but with halakhic change needing to be agreed upon by committee, then a lot of Gillman’s broader case falls into place. Many, if not all, of Gillman’s questions about dealing with inconsistency are answered because there need not be halakhic consistency in a Movement that sees Halakhah as a tool of expression rather than a divinely-given and eternally binding system.

We will return to Gillman’s case in future entries of this series. For now we will focus on the fact that this telling of the Movement’s history is far from uncontested.

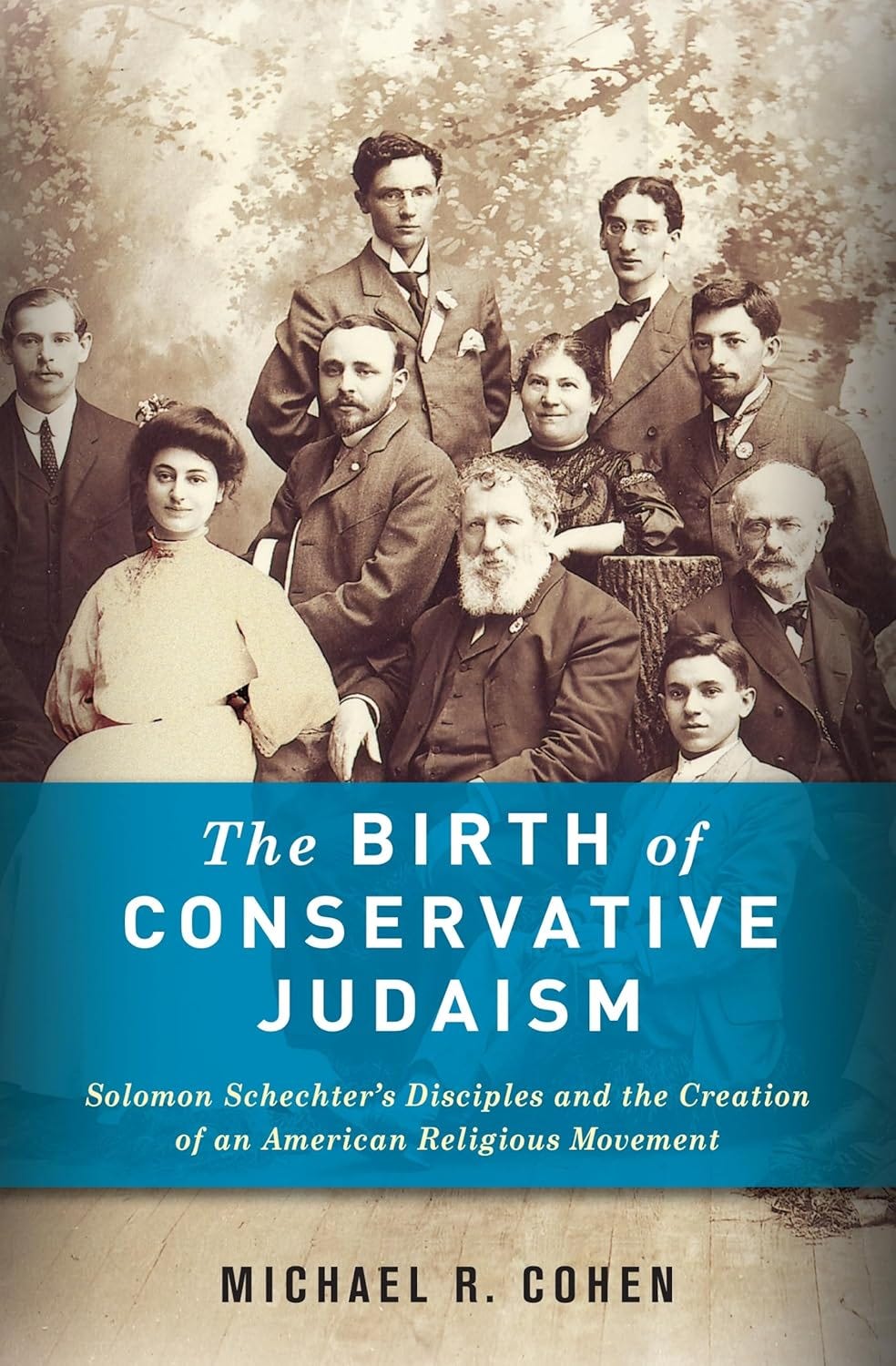

The most articulate critic of the above formulation is Professor Michael R. Cohen, head of Jewish Studies at Tulane University and author of 2012 book, The Birth of Conservative Judaism: Solomon Schechter’s Disciples and the Creation of an American Religious Movement.

Cohen begins by challenging the popular assumption that Orthodoxy is the youngest of the three main Jewish denominations. He points out while the Conservative Movement is widely perceived as being over a century old, the term was actually “vague and undefined” for much of the early twentieth century while Reform and Orthodox articulations of Judaism were relatively clear-cut. This, Cohen argues, was by the design of none other than Solomon Schechter himself:

Those who support the historical school theory generally argue that when [Frankel’s] historical Judaism came to America, it was institutionalized at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTS), which would in time become the training seminary for the Conservative rabbinate. The Jewish Theological Seminary was originally founded in 1886 when a group of traditionalists rejected the more progressive Hebrew Union College. In its early years the Seminary was plagued by low enrollment and financial difficulty, but in 1902 Solomon Schechter was hired to lead the fledgling institution, which quickly grew and came to be informally known as Schechter’s Seminary. There is no question that aspects of historical Judaism deeply influenced the leaders of JTS, as Schechter himself was committed to its ideas and so, too, were the faculty and students. Yet those affiliated with Schechter’s Seminary were not the only American Jews to support historical Judaism - leaders of the Orthodox Union (OU), which was closely affiliated with the pre-Schechter seminary but broke away after Schechter’s arrival, also initially professed their support for the idea.

While many of those connected with Schechter’s seminary supported the concept of historical Judaism in theory, not everybody could agree on just how to implement it in practice. Who, for example, would have the authority to adapt Jewish law to modern circumstances, and what criteria would they use for such changes? Schechter understood that historical Judaism “has never, to my knowledge, offered the world a theological platform of its own,” and he offered the concept of “Catholic Israel,” or the united people Israel, as a means by which the idea of historical Judaism could be implemented. He maintained that only a unified Jewry had the authority to adapt Jewish law to its modern surroundings and that no individual group or sect had the authority to do so. Because a third movement in Judaism would therefore have had no power to adapt Jewish law to its surroundings on its own, Schechter eschewed the creation of a distinct third movement and instead strove for a unified community that could affect the change he desired.

While a clear-cut articulation of who counts as part of Catholic Israel is hard to find, Cohen collects various clues from Schechter’s voluminous writings:

Schechter’s writings and speeches are replete with references to this idea of unity, which became one of his most important guiding principles. Judaism, he maintained, is “as wide as the universe, and you must avoid every action of a sectarian or of a schismatic nature.” He rejected “any adjectives to my Judaism, believing that I belong to the main stream of Judaism, which meant an orderly and regular development in accordance with our laws and traditions… To that extent, I am a Jewish man and not a party man.” When he later arrived in America, he argued that he wanted JTS to be “broad enough to harbor the different minds of the past century,” to attract “the mystic and the rationalist, the traditional and the critical,” and to be “all things to all men, reconciling all parties, and appealing to all sections of the community.”

While Catholic Israel implied Jewish unity, Schechter also applied it to the development of Jewish law. By emphasizing the past, he developed a model for how halacha could adapt to its contemporary surroundings. Schechter was a believer in historical Judaism - the idea about which we have already spoken, that Jewish law had always adapted to its contemporary surroundings. Therefore he argued that because the interpretation of Scripture is “mainly a product of changing historical influences, it follows that the centre of authority is actually removed from the Bible and placed in some living body, which, by reason of its being in touch with the ideal aspirations and the religious needs of the age, is best able to determine the Secondary Meaning.” Reflective of his emphasis on unity, he maintained that that living body “is not represented by any section of the nation, or any corporate priesthood, or Rabbihood, but by the collective conscience of Catholic Israel as embodied in the Universal Synagogue.” The Universal Synagogue, comprised of teachers and prophets, psalmists and scribes, among others, was “the only true witness to the past, and forming in all ages the sublimest expression of Israel’s religious life, mist also retain its authority as the sole true guide of the present and the future.” Thus Schechter believed that Jewish law could change, but only with the blessing of the unified Jewish community.

Catholic Israel, then, must take into account the practices of those who are both observant and non-observant, and must change naturally with both perspectives in mind. Allowances should not be made simply because most decide to ignore Halakhah while stringencies should not be implemented to only serve the most pious. In order for this balance to be struck, representatives of both Reform and Orthodoxy had to share one unified Jewish community (and ideally have one shared rabbinic institution). Assumptions that the Seminary had strict boundaries (even those of Frankel’s school) from the get-go, in Cohen’s words, “suffer[s] from “deceptive retrospect,” ignoring the goals and actions of the movement’s founders. While the Conservative movement may have been committed to historical Judaism, it tied this concept to Catholic Israel, which opposed the creation of a movement that would distinguish itself from both Reform and Orthodoxy.”

What held the movement together for so long was primarily Schechter’s charismatic leadership. “Schechter,” Cohen wrote, “came to the Seminary as one of the world’s best-known Jewish scholars, captivating those in his presence and creating an aura around him that rarely disappointed.” He “had a simple, albeit idealistic, vision for American Judaism that he passed down to his disciples” of “a community committed to traditional Judaism, yet one adapted to America through the incorporation of English, decorum, and modern education. He also wanted his disciples to work together to achieve this and unite the American Jewish community in the image of Catholic Israel.”

Schechter’s “maintenance of deep personal and social bonds” as well as “the embrace and institutionalization of diversity” he championed allowed his varied students to feel comfortable not only with him, but with each other despite not falling into one camp. As Cohen points out,

Some of Schechter’s disciples identified as conservative, and others identified as orthodox, and their beliefs and practices spanned much of the spectrum of American Judaism. While we can broadly define Schechter’s disciples as either conservative or orthodox, the terms that they used to describe themselves varied widely. For example, many self-identified conservative also used the labels progressive or liberal, loosely referring to themselves as the left wing of the emerging movement. Those who identified as orthodox also used the terms modern orthodox or traditional, often referring to themselves as the right wing of the merging movement. Still others called themselves centrist… Disciples formed coalitions to broadly affect change, and this fluid terminology highlights the diversity and elasticity of the emerging Conservative movement over the first half of the twentieth century.

This diverse group largely stayed together, however, due to their shared bonds and affinity for their mutual teacher. Back to Cohen,

Clearly Schechter’s disciples were diverse in their practices and their identities, yet the social bonds about which we have spoken, and the vague group consciousness that those bonds created, played a critical role in overcoming this diversity and keeping the group unified. This group consciousness was further strengthened and institutionalized in the United Synagogue of America, which today serves as the congregational arm of the Conservative movement. Upon its founding in 1913, however, and for its first decade, at the very least, it was an organization led by Schechter’s rabbinical disciples with the purpose of implementing their teacher’s vision. By transferring his authority to the diverse executive council of the United Synagogue, rather than to a single heir, Schechter effectively institutionalized Catholic Israel and ensured that it would be a central tenet of the emerging movement. All could hold a leadership position, irrespective of background or viewpoint, provided they both ascribed to Schechter’s vision and were committed to implementing it as a group. The strength of the United Synagogue lay in the fact that, despite much diversity, Schechter’s disciples believed that they could more effectively carry out Schechter’s vision - however differently they interpreted it - through the organization they viewed as his legitimate heir.

Again, the focus on group consciousness is clear - neither the left nor right wings of Schechter’s students were given full reign. They were expected to work together and implement a form of Judaism that was mutually agreed upon and negotiated rather than driven too much by one or the other. This also meant growing their shared vision by reaching out both to the burgeoning Reform and Modern Orthodox communities:

While internal diversity characterized the disciples and their United Synagogue, so too did the quest for Catholic Israel and unity within the broader American Jewish community. This meant reaching out to Reform rabbis and congregations in an attempt to bring them closer to traditional Judaism, and many of the disciples served in Reform congregations, with varying degrees of success. Their experiences demonstrate that the boundary between the Reform movement and the emerging Conservative movement was much more porous than many historians have previously recognized.

That may seem to affirm Gillman’s contention that Conservative and Reform always shared a fundamental understanding of Halakhah, but Cohen notes that things were equally porous between Conservative and Orthodoxy:

Orthodoxy was institutionally divided, and the United Synagogue was not the only organization for modern Orthodox rabbis and congregations. Instead, they were also represented in the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America, now known as the Orthodox Union (OU). The OU had been closely aligned with the Seminary before Schechter’s arrival, and its leaders had a somewhat adversarial relationship with Schechter. Although, in the name of Catholic Israel, the disciples hoped to affiliate modern Orthodox rabbis and congregations affiliated with the OU, they had a difficult time doing so. As we will see, without an allegiance to Schechter, the OU rabbis generally chose not to join the United Synagogue.

[However,] the reality was that there was a tremendous amount of overlap between the United Synagogue and the OU. The United Synagogue was a coalition of Conservative and modern Orthodox rabbis, and many OU leaders maintained that their organization differed from the United Synagogue because it expressly repudiated non-Orthodox practices. Yet while this may have been the case in theory, it was not always the case in practice. For example, though the OU viewed mixed seating to be outside the scope of Orthodoxy, it nevertheless accepted vast numbers of rabbis who served in mixed-seating congregations. By one 1951 estimate, half the graduates of the OU’s primary training seminary served in mixed seating congregations. The result was that the distinction between the United Synagogue and the Orthodox Union rabbis and congregations was not always clear.

More than superficial similarities, Cohen points out that “it was virtually impossible to distinguish a member of one group from the other based solely on their particular beliefs” and that “the practices of OU rabbis were virtually indistinguishable from Schechter’s modern Orthodox disciples.” Indeed, “the OU and the United Synagogue competed for the same niche in the early decades of the twentieth century, as, arguably, the Conservative and Reform movements do today.” The primary divider between the right wing of the early Conservative Movement and Modern Orthodoxy, then, was simply “whether or not a rabbi chose to identify with the United Synagogue.” Even the founding aims of the United Synagogue, agreed to by all its founders, reads largely similar to what one might expect from an Orthodox body:

To assert and establish loyalty to the Torah and its historical exposition,

To further the observance of the Sabbath and the Dietary Laws,

To persevere in the service the reference to Israel’s past and the hopes for Israel’s restoration,

To maintain the traditional character of the liturgy, with Hebrew as the language of prayer,

To foster Jewish religious life in the home, as expressed in traditional observances,

To encourage the establishment of Jewish religious schools, in the curricula of which the study of the Hebrew language and literature shall be given a prominent place, both as the key to the true understanding of Judaism, and as a bond holding together the scattered communities of Israel throughout the world.

One prominent example of a JTS graduate who chose to affiliate with the OU instead of the United Synagogue was Rabbi Herbert Goldstein, who would become the first (and thus far only) to be elected president of the OU, RCA, and Synagogue Council of America in his lifetime. A Son-in-law of Harry Fischel, Cohen notes how Goldstein’s wedding was jointly officiated by Rabbis Solomon Schechter, H. Pereira Mendes (minister of Shearith Israel and one of the OU’s founders), and Moshe Zevulun Margolies (“the Ramaz,” a founder of and leader in the Agudah).

How, then, did Orthodoxy and Conservatism part ways? How did Conservative Judaism turn into exactly what it was not meant to be?

It can initially be traced, perhaps, to Schechter’s decision to fire faculty carry-overs from the Seminary’s initial iteration early in his tenure. Rabbis Henry Pereira Mendes and Bernard Drachman were both retained after the institution’s restructuring but nevertheless fired by Schechter due to not meeting his scholarly standards. The two “were deeply disappointed by their treatment at the hands of Schechter and, following their dismissal, they revitalized and led the Orthodox Union. Their estrangement from the Seminary orbit helped split the modern Orthodox world in tow, which… would have vast implications on the separation of Orthodox and Conservative Judaism.”

Matters were not helped by a 1925 controversy surrounding Rabbi Solomon Goldman, a JTS-graduate who identified strongly as “Conservative” and issued many changes at the Cleveland Jewish Center. Several of Goldman’s congregants took him to court on the claim that the CJC’s constitution specified that shul services “must be held in conformity with the orthodox law,” but that Goldman changed it to “ignore all reference to Orthodox Judaism” and instead “promulgate and protect the doctrines of Conservative Judaism.”

The congregants accused Goldman of no less than 38 ways in which he was “opposed and hostile to the doctrine of Orthodox or traditional Judaism and all the ritual and ceremonial observance appertaining thereto” which included his publicly denying revelation, omitting the Grace after Meals at congregational dinners, preventing the recitation of Birkat Kohanim on holidays, disallowing the congregation to rise when the Ark was opened, calling congregants to the Torah using their aliyah number rather than their Hebrew name, instituting mixed seating in the congregation, and more.

The OU called on the United Synagogue to condemn Goldman, believing this gave them a chance to finally “indicate where their sympathies lie” and unify Modern Orthodoxy. The United Synagogue, for their part, “understood that silence would alienate OU rabbis, and perhaps even some within their own ranks” but chose to reiterate their stance as being “committed to a comprehensive policy embracing all types having a common aim, however much they may differ in their views as to non-essentials.” This resulted in the OU’s officially regarding the United Synagogue as a non-Orthodox body.

When various Orthodox Seminary graduates later sought membership or partnership with the OU, they were often given a cold shoulder if they already affiliated with the United Synagogue, whose institutionalized diversity proved to be its Achilles heel:

Though Schechter’s disciples sought unity in the image of Catholic Israel, they were nevertheless resoundingly rejected by the rest of the American Jewish world - particularly by rabbis in the OU and the Agudath ha-Rabbanim. These rabbis cast aside the United Synagogue as an organization hostile to Orthodoxy precisely because it sought unity and welcomed anyone who wished to join - even if they did not follow Orthodox practices. They diligently tried to articulate the boundaries between “Conservative” and “Orthodox” practices, defining in particular mixed seating as antithetical to Orthodoxy. Such definitions of deviant behavior… could have helped OU leaders to strengthen what was at the time a rather weak organization. This practice of defining deviant behavior has long characterized boundary maintenance among Orthodox Jewish groups. Nevertheless, because the United Synagogue did not repudiate these deviant, “non-Orthodox” practices, both the OU and the Agudath ha-Rabbanim felt justified in spurning the United Synagogue. Thus… in their quest for unity, Schechter’s disciples were ironically forced by the right into a movement of their own.

Internal tensions were exacerbated as lay leadership took over the United Synagogue and halakhic debates moved to within walls of the Rabbinical Assembly. Through the RA, “Orthodox and Conservative disciples debated their different conceptions of the movement, and they discovered that their needs and goals conflicted with one another’s.” The Orthodox members still hoped to build bridges with the OU and “continued to oppose any decisions by the United Synagogue that might give these other Orthodox rabbis more reasons to reject them.” The alliance held together by a thread because although the Conservative disciples “hoped to define a platform for the United Synagogue that distinguished it from these other Orthodox rabbinical associations,” they also “refused to alienate the modern Orthodox disciples within their coalition - with whom they shared social bonds and a common mission.” The search for common ground between sides proved to be futile, though, as all parties came to realize that “the only common factor which held them together was their shared commitment to the Seminary - which had been shaped by Schechter - and their common identity as a result of their affiliation with it.”

It should come as no surprise whatsoever that the next generation of rabbis, who had neither the same relationship with Schechter nor the commitment to Catholic Israel he would have imbued in them, felt the state of the young movement untenable. In Cohen’s words,

This new generation insisted on defining the boundaries of a distinct third movement of American Judaism, and they began this process by producing a prayer book that unified the emerging movement as no previous book had. Shortly thereafter, this new generation of JTS rabbis fundamentally redefined the movement that had been created by their predecessors by jettisoning the commitment to Catholic Israel. They created the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards (CJLS) in 1948, which boldly declared that it would no longer seek the approbation of the other Orthodox rabbinical associations. In 1950 that committee declared it acceptable to drive to synagogue on the Sabbath and/or use electricity on the Sabbath - both of which violated traditional Orthodox law. This represented a shift to the idea that the RA itself could change Jewish law without the permission of Catholic Israel. No longer would the emerging Conservative movement be defined by Catholic Israel and a quest for inclusivity; it would now stand on its own. This fundamentally redefined the Conservative movement, abandoning its founders’ intentions, as it increasingly became a third, distinct, movement in Judaism.

The rest, as they say, is history. We saw in our last entry how consistent shedding of the movement’s right wing led to progressively greater shifts away from mainstream Halakhah and thus further alienated Conservative traditionalists. As a famous quote says, those who do not remember history are doomed to repeat it and this has surely been the case time and again in the Conservative Movement. Cohen argues that this is unsurprising. Indeed,

while the next generation of rabbis was redefining the movement, some of them fell victim to deceptive retrospect and assumed that the movement had always intended to have unique boundaries that marked it off as distinct. As a result, they began to write the history of their movement not as it actually occurred but rather as if Catholic Israel had been merely a temporary stumbling block instead of the essence of the movement. This marginalized Schechter, and these rabbis now turned to Germany and found in Zacharias Frankel a new inspiration for their movement.

Such deceptive retrospect (which Cohen clarifies in an endnote was likely unintentional) effectively “created the myth that the Conservative movement always had clear boundaries and a distinct ideology” while also making it incredibly easy to justify claims that the Conservative movement need not maintain fealty to a binding halakhic system, as those we examined last week have argued. Eventually, the Rabbinical Assembly formed a new committee on Jewish Law and Standards, which stopped attempting to appease traditionalists altogether:

Seeking to continue the policy of previous committees, Louis Epstein offered a resolution that the new RA committee “shall be instructed to hold itself bound by the authority of Jewish law and within the frame of Jewish law.” Such a statement would certainly allow the modern Orthodox disciples to at least claim the RA was not antithetical to Orthodoxy. Yet, in perhaps its most provocative move yet, the RA rejected the resolution; instead, the new committee would be committed to “the raising of the standards of piety, understanding, and participation in Jewish life.” This was a monumental change that indicated a willingness to alienate the traditional, modern Orthodox disciples for the sake of a platform and a preparedness to break definitively with rabbis in the OU and Agudath ha-Rabbanim.

Looking to history with an objective lens, as Cohen masterfully does, reveals a much more complicated picture and raises serious questions about not only how the Conservative movement ought to view themselves, but also how Orthodoxy ought to respond to those they disagree with. This is especially so as Modern Orthodoxy currently navigates the differing perspectives and institutional affiliations of so many of Rav Joseph. B. Soloveitchik’s self-identified disciples (Stay tuned for my forthcoming review of Daniel Ross Goodman’s Soloveitchik’s Children: Irving Greenberg, David Hartman, Jonathan Sacks, and the Future of Jewish Theology in America). Realizing the different directions that America’s Jewish denominational story could have gone may help pave the way for a brighter future. Now that we are about to enter the Nine Days, that is an important message to end on.

Our next entry into this series will delve into different arguments for the Conservative Movement’s relationship with Halakhah, followed by debates about how Halakhah and theology ought to interact. As Conservative Judaism continues to face new questions, Cohen is no-doubt correct in his conclusion:

Struggling between a commitment to tradition and a desire for change, between those who advocate for a broadly encompassing “big tent” movement and those who seek a more narrowly defined, ideologically coherent one, the Conservative Movement faces difficult choices. It will be best prepared to confront them if it understands itself historically and appreciates the way in which Schechter’s disciples created this American religious movement.”

(Postscript 1: Cohen’s book is one of the best I have ever read, not only because it affirms the history of Conservative Judaism I grew up with rather than what many have tried to tell me, but because of how thorough and enjoyable of a read it is. It’s rare for a scholarly book to read like a novel, but this one does a superb job. I encourage anyone who made it this far to try to pick up a copy.

Postscript 2: A few people have reached out accusing me of using this series to “punch down” and attack the Movement I grew up with. I want to emphasize that this is NOT the case. I genuinely feel that there is much for Orthodox Jews (my primary readership) to learn from the history of the Conservative Movement and the debates within it. It is my aim to present those debates as faithfully as possible. This series is not meant to tell the Conservative Movement what direction I think it should move in - I forfeited any right to a vote on that when I decided not to send in my application to JTS’ rabbinical school. While I am glad that Conservative Jews are engaging with my writing, and I greatly value that I still have something to say that people within the Movement deem worth listening to, these articles are not necessarily meant for you.)