Given my background, one of the most frequent questions that I’m asked is what the difference is between Orthodox and Conservative approaches to Halakhah. My last essay reviewed two recent book from the Orthodox world that multiple readers pointed out sounded “Conservative” to them. I understand where that understanding comes from - Rav Hershel Schachter’s view of the Oral Torah being part of the Written Torah might be seen as an inversion of JTS Bible Professor Ben Sommer’s understanding of the Written Torah as being part of the Oral Torah. Likewise, the approach outlined by Rabbi Shmuel Phillips sounds aligned with the presumed Conservative position that there is room to adjust anything after the sealing of the Talmud on first read. This essay will clarify the Conservative Halakhic process by calling attention to the work of one of its staunchest and most erudite expositors.

Before exploring that, though, it’s important to look at how these two denominations parted ways. Professor Michael R. Cohen’s The Birth of Conservative Judaism: Solomon Schechter’s Disciples and the Creation of an American Religious Movement does an extraordinary job examining that split.

Cohen explores Schechter's arrival in the US to take over the Jewish Theological Seminary and its transition from Spanish & Portuguese “Enlightened Orthodoxy” to the bastion of Conservative Judaism it is today. Cohen masterfully recounts how

Schechter's disciples sought unity in the image of Catholic Israel [avoiding decisions that would alienate either religious extreme], [but] they were nevertheless resoundingly rejected by the rest of the American Jewish world - particularly by rabbis of the OU and the Agudath Ha-Rabbonim. These rabbis cast aside the United Synagogue as an organization hostile to Orthodoxy precisely because it sought unity and welcomed anyone who wished to join - even if they did not follow Orthodox practices.

As Schechter's direct disciples died out, the movement they formed became more willing to craft their own line and alienate those who disagreed. They "held a fundamentally different view of the movement than the disciples and they redefined it in a way they hoped would distinguish it from Orthodoxy." In so doing,

these rabbis marginalized Schechter, whose inclusivity and Catholic Israel stood in the way of what they hoped their movement would become. Instead, they mistakenly assumed that the movement always intended to be a third movement, distinct from the others, and many believed that Schechter's Catholic Israel had been an obstacle. To support this assertion, they went back in time to the German historical school and began to view Zecharias Frankel as the "founder" of their movement. By valuing Frankel over Schechter... this next generation fell victim to deceptive retrospect and created the myth that Conservative Judaism had always been a movement with clear boundaries. This myth still persists and, as we have seen, nothing could be farther from the truth.

As I reflected when I first received Cohen’s wonderful book, this topic hits me close to home. I grew up identifying Conservative Judaism with a diverse movement that prided itself on included a plurality of views. I could not fathom a Conservative Movement that did not welcome traditional prayer services, Shabbat and Kashrut observance, etc. I also grew up taking for granted that the movement started as essentially Modern Orthodox. Cohen’s work affirms that largely forgotten narrative, and I couldn't help but see my own path towards Orthodoxy reflected as more members of the United Synagogue felt pushed towards the Orthodoxy over time.

Cohen concludes his book with an important consideration for future of the Conservative Movement:

Struggling between a commitment to tradition and a desire for change, between those who advocate for a broadly encompassing "big tent" movement and those who seek a more narrowly defined, ideologically coherent one, the Conservative movement faces difficult choices. It will be best prepared to confront them if it understands itself historically and appreciates the way in which Schechter's disciples created this American religious movement.

Many leaders of the Conservative Movement have understood this over the years. I’ve already mentioned elsewhere Rabbi Baruch Frydman-Kohl’s quasi-prophetic quote that embracing the “liberal conception of Jewish law” that the Movement now champions such a “will have a long-term impact on whether traditionalists will remain part of the movement, seek to become Conservative rabbis, or whether they will be led to find another place in the landscape of Judaism.”

This is particularly important as Conservative Judaism appears to move closer to divesting itself from the Halakhic process entirely by the day. In the words of Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove (Senior Rabbi at Park Avenue Synagogue - arguably the Conservative Movement’s Flagship house of worship), most Jews understand mitzvot as

volitional lifestyle choices, not commanded deeds existing within the totality of a halakhic system. And while my observations are those of a Conservative rabbi, I would contend that the difference between Reform, Conservative, and Modern Orthodox Jews is a difference of degree and not of kind. Everyone is picking and choosing… Judaism has become a buffet prepared to serve the individual tastes of the contemporary Jew.

R. Cosgrove then suggested that “the Conservative movement should disabuse itself of the belief that its devotees are halakhic and rename its Committee on Jewish Law and Standards [to] the Committee on Jewish Life and Spirit, with its sole focus to inspire, educate, and empower Jews towards a life of religious observance.” Furthermore, “all movements would do well to reorient their arguments for observance away from the thought that anyone is required to do Jewish.” they also “must eschew an all or none attitude when it comes to observance and affirm every Jew’s autonomous decision to embrace a life of mitzvot, both meeting people where they are and inspiring them to live the Jewish life they seek, even if that life is not, strictly speaking, halakhic.”

This is very much aligned with the late Rabbi Dr. Neil Gillman, a close student of Mordecai Kaplan, who called out the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism in 2005 for the Movement’s inconsistent identification with Halakhah (expanded and printed in Doing Jewish Theology: God, Torah, and Israel in Modern Judaism). He argued that it was disingenuous for Conservative Judaism to identify itself as a Halakhic movement. In his words, "it is a totally idiosyncratic use of the term, unrecognizable by Jews who take halakhah seriously in their personal lives. It is in effect a subjective, emotional outburst, a covert way of saying, “It’s great to be a Conservative Jew,” or “I’m proud to be a Conservative Jew,” which is totally legitimate, as long as we realize that this is what we are doing. We are simply describing how we feel about ourselves." He went on, pulling no punches:

My critique of the claim that we are a halakhic movement is directed not at how we function but how we identify ourselves... the claim is unfalsifiable and disingenuous, it escapes any clear definition, it has failed to engage our laity who either don’t understand it or don’t view it as relating to their own lives, and it is subverted by the culture of our movement, by its academic center, and by its implicit theology. It is a claim, created by and for rabbis and designed primarily to promote our wish to feel authentic... if we deny the historicity and the literalness of the Sinai narrative as it appears in Torah, and if we claim that the Jewish religion was essentially the creation of the Jewish people, of groupings of Jews at various critical moments in our history, functioning in response to and within specific cultural contexts which we can describe... then we must conclude that authority in matters of belief and practice lies within the hands of the committed Jews of every generation.

What, then, separates Conservative Judaism from explicitly non-Halakhic movements? In Gillman’s words,

We differ in how much of traditional Jewish ritual practice we want to retain, how much we are prepared to abandon or to change, and how we go about changing. In all of these areas, we are more “conservative.” That is more of an emotional stance than a theological one, and it is thoroughly legitimate on its own terms. Feelings are important.... No one who has davened in a Reform or in a Conservative synagogue could possibly confuse the two. I have frequently suggested that were you to blindfold me and lead me into five Reform and five Conservative synagogues, I would identify the movement in less than a minute. Whatever my personal theology, I cannot daven in a Reform or Reconstructionist synagogue or from one of their siddurim. None of this is going to change.

Despite these critiques, the CJLS still exists and, by its own description, “sets halakhic policy for Rabbinical Assembly rabbis and for the Conservative movement as a whole.” Here is how that process works:

The Committee discusses all questions of Jewish law that are posed by members of the Rabbinical Assembly or arms of the Conservative movement. When a question is placed on the agenda, individual members of the Committee will write teshuvot (responsa) which are discussed by the relevant subcommittees, and are then heard by the Committee, usually at two separate meetings. Papers are approved when a vote is taken with six or more members voting in favor of the paper. Approved teshuvot represent official halakhic positions of the Conservative movement. Rabbis have the authority, though, as marei d'atra, to consider the Committee's positions but make their own decisions as conditions warrant. Members of the Committee can also submit concurring or dissenting opinions that are attached to a decision, but do not carry official status.

This policy of passing responsa with only a six-vote minimum has led to no shortage of fascinating situations. Rabbi Amy Levin noted one when she was a Scholar-in-Residence at my parents’ Conservative synagogue. In 2013, a teshuvah concluding that opening and closing the ark in synagogue “should be done in a meaningful way by Jew and non-Jew alike” passed with 8 votes. However, a different teshuvah in 2016 concluded unequivocally that this act “must be reserved for Jews” and passed with 12. These contradictory teshuvot are right next to each other on the CJLS website.

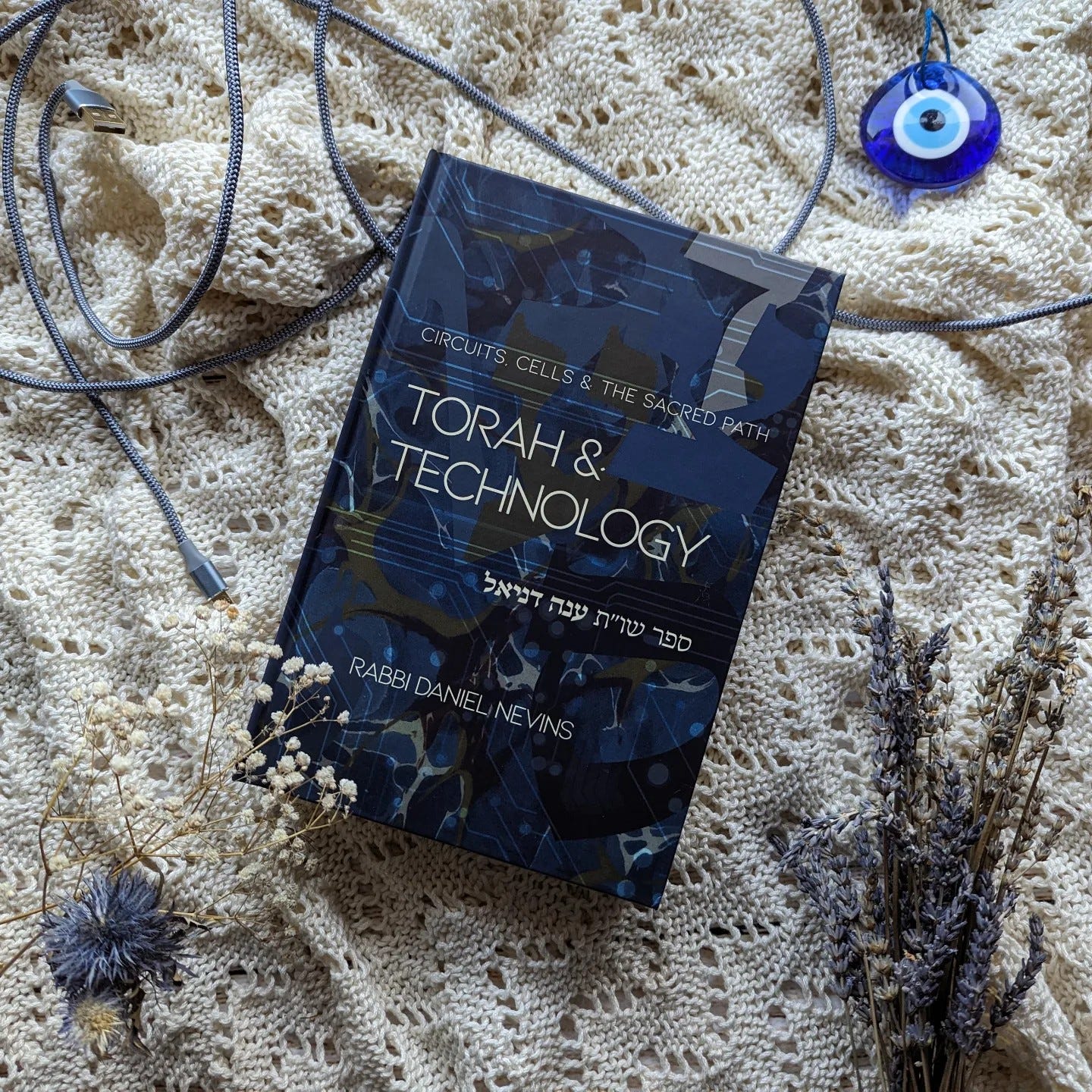

With this background, we can explore several positions of Rabbi Daniel Nevins. R. Nevins is Head of School at Golda Och Academy in West Orange, New Jersey, one of the leading Conservative Day Schools in North America. He was previously Dean of the Jewish Theological Seminary’s Rabbinical School and served on the CJLS for 25 years. R. Nevins is a student of Rabbi Joel Roth, who is known to be one of the most “conservative” voices within the Movement regarding Halakhah. Many of R. Nevins’ teshuvot were published in Torah and Technology: Circuits, Cells, and the Sacred Path (Izzun Books, 2024), which I cannot recommend enough if one wants to understand how Conservative Halakhah is determined in the face of modern challenges. R. Nevins writes that although the teshuvah genre is largely unknown to Conservative laypeople, it is more important to connect with such writings now than ever:

As the pace of change accelerates, the importance of ancient wisdom increases. The vast literature of Torah contains insights that can guide us in our own path to virtue, especially when the territory we traverse seems unlike the regions crossed by our ancestors. Their resilience and resolve, their ability to reconfigure Jewish life despite dislocations and discontinuities, can fortify and guide us today… halakhic literature is especially well suited for responding to shifting circumstances while retaining the core values and norms of our ancestors.

Indeed, given that the Conservative Movement has “has nothing to do with politics, and little to do with today’s cultural conservatism,” Rabbi Nevins supports Rabbi Daid Wolpe’s suggestion to rebrand as Covenantal Judaism, “since this title would more accurately reflect our commitment to join the people of Israel to God and each other through the study of Torah and the practice of mitzvot and acts of kindness.”

The natural question is whether a Conservative/Covenantal approach can succeed in prioritizing the importance of halakhah or if the movement should end up where, in Cosgrove’s words, rabbis spend their days “leading Jews who live non-halakhic lives, but who, nevertheless, aspire towards halakhic moments. Jews for whom Jewish practice is episodic, opportunistic, and located predominantly in life’s poetic moments: birth, death, festivals. Jews who live comfortably with the gap between their personal practice and the standard practiced and preached by their clergy.”

We’ll approach this question by examining several of Rabbi Nevins’ halakhic conclusions in conversation with one another. It is highly recommended to read the full book in order to best understand the factors which led to his conclusions.

The Kashrut Status of Lab-Grown Meat

In 2017, Rabbi Nevins addressed the question “may cultured meat - also known as in vitro, clean, cultivated, or lab-grown meat - be considered kosher?” It was approved by the CJLS with 21 votes. Rabbi Nevins concludes as follows:

Should cultured meat become a viable consumer product, it will be important to ascertain that it derives from a kosher species of animal and that the growth medium and any additives be plant-based or synthetic and certified kosher. Indeed, the entire process will require kosher supervision.

Cultured meat derived from cells taken from a kosher species of animal will not be prohibited as a limb or flesh taken from a living animal, because the original cells will not be eaten, and they alone would not suffice to create the final product.

While cultured meat might be deemed pareve like eggs, because the product is designed to mimic the biological structure and eating experience of pastured meat, it would be confusing for one meat to be besrai and another apparently identical meat to be pareve. If a transition is completed away from the marketing of conventional pastured meat in favor of cultured meat, then this marit ayin concern may be removed, just as concerns related to using almond milk with meat dishes have been eliminated.

If cultured meat fulfills the promises of being less cruel to animals, less destructive to the environment, and more healthful to consume, then it will be not only acceptable, but even preferable to eating conventional pastured meat.

Of particular interest is Rabbi Nevins’ third conclusion, a stringent ruling is warranted to avoid the confusion that would come with some meats being considered pareve while others are basari. What happens when such a concern is not invoked?

Electronic Devises and Cars on Shabbat

One of the easiest ways to tell most Orthodox and Conservative Jews apart is by asking what they consider to be acceptable to do or not do on Shabbat. An infamous example of this is the 1950 “Responsum on the Sabbath” which allowed Conservative Jews to drive to and from synagogue.

Lately, with JTS frowning on their students who hold by that responsa, use of electricity in the home on Shabbat is a much clearer division. The CJLS accepted Rabbi Nevins’ teshuvah on the subject in 2012, with 17 votes. The conclusions are as follows:

Considerations of Melakhah

The operation of electrical circuits is not inherently forbidden as either melakhah or shvut. However, the use of electricity to power an appliance that performs melakhah with the same mechanism and intent as the original manual labor is biblically forbidden on Shabbat. For example, grinding coffee, trimming trees, sewing, etc, are all forbidden with electrical appliances in the same way that they are forbidden without the use of electricity, as an av melakhah.

The use of electricity to perform an activity with a different mechanism but for the same purpose as a melakhah is forbidden to Jews on Shabbat as a derivative labor (toledah). Such prohibitions share with the primary forms the severe status of being biblically forbidden. Thus, cooking with an electric heating element or a microwave oven on Shabbat is forbidden as toledat bishul, though it is permitted on Yom Tov. Recording text, sound images, or other data with an electronic device is forbidden as toledat koteiv, a derivative form of writing. Sabbath and Yom Tov operation of any electronic recording device, camera, computer, tablet, or cellular phone is forbidden by this standard. Moreover, the creation of a durable image, as with a printer, is also forbidden as a derivative form of writing. Automation may be employed prior to Shabbat to set some such processes in motion, but even here, one must be cautious about the temptation to adjust such devices, as well as their capacity to undermine the distinct atmosphere of Shabbat.

For the sake of protecting life, even biblical prohibitions are superseded. Thus, all electrical and electronic devises needed to administer medicine and medically necessary therapies or to summon medical assistance are permitted on Shabbat. If a health challenge is not life-threatening, then Jewish people should not perform melakhot, but it may be permissible to employ non-Jewish assistants to use automated systems to help the patient.

Considerations of Shvut

The positive commandment of shvut, to rest on Shabbat, demands a day of differentiation, in which one avoids commerce, the creation of loud sounds, and anything that would replicate the atmosphere of the work week. electrical appliances like fans, light fixtures, and magnetic key cards and fobs may be used without violating either the law or the spirit of Shabbat. However, when it comes to electronic communication devices, even if some are not forbidden as a form of melakhah, the tranquility of Shabbat may be compromised by such activities. Rabbinical teachings indicate that Shabbat should be dedicated to prayer, Torah study, meals, and rest, not to weekday concerns. We ought to anchor our day in physical environments such as the synagogue and dinner table, that reinforce the holy nature of the day and allow its spiritual potential to be realized. However, Sabbath-observant people can be trusted to decide what formally permitted activities are consonant with their Shabbat tranquility.

Positive halakhic values such as protecting human dignity, avoiding excessive strain, financial hardship, and the squandering of natural resources may supersede the rabbinic restraint on using electricity as indicated by shvut. Calling an isolated or ill individual might be permitted as an act of hesed and an expression of honoring parents. The use of electrical motors to assist frail and disabled people to move around, and use of assistive devices to enhance hearing, speech, and vision, may be justified based on the imperative to protect human dignity, despite the possibility that such tools might lead one to an activity that is rabbinically banned. The use of elevators to reduce strain on Shabbat is likewise permitted. Turning off electrical appliances is permissible to avoid financial hardship and the wasting of natural resources (in contrast to extinguishing a fire, which is not permitted to save fuel). In such cases, halakhic imperatives such as protecting human dignity, avoiding excessive strain, and conserving resources may supersede rabbinic restrictions (shvut) but not biblical prohibitions (melakhah).

Refraining from operating lights and other permitted electrical appliances is a pious behavior that can prevent inadvertent transgression and reinforce the distinctiveness of Shabbat. In many of our communities, a ban on operating all appliances, including lights, has become the operative practice, and should therefore be maintained. Those who do make limited use of electricity must be attentive to the distinctions explained in this responsum, avoiding any activities that would result in cooking, recording, or other labors on Shabbat. They also would be well-advised to be sensitive to the practice of visitors who seek to avoid any operation of circuits, and they may wish to defer to the more stringent practice of much of the observant community. In this way, Shabbat may provide its observers with a distinctive day of delight, dedicated to prayer, Torah study and fellowship. Then Shabbat will continue its powerful role as a sign pf the covenant between God and Israel, transmitting holiness from generation to generation, and supporting the creation of sacred communities.

While it is clear that Rabbi Nevins went to great effort to outline the importance of traditional Shabbat observance, the degree of nuance in his highly influential teshuvah has led to much confusion amongst those who have attempted to implement his ruling. One recent example was the 2023 decision by the CJLS to approve two mutually-exclusive teshuvot about electric cars on Shabbat. Rabbis David Fine and Barry Leff ruled that driving one “is not a violation of Shabbat as long as the driving is not for non-Shabbat purposes.” Their “Renewed Responsum on the Sabbath” was approved with 10 votes. On the other hand, Rabbis Mordechai Schwartz and Chaim Weiner ruled in their own “New Responsum on the Sabbath” that “driving an automobile on Shabbat [is] uniformly prohibited to all Jews, unless there was an intent to perform a mitzvah or out of concern for health or safety… regardless of its manner of propulsion.” This more restrictive position passed with 11 votes. In Torah and Technology, Rabbi Nevins shares his personal opinion:

all Jews ought to prioritize walking on Shabbat and Yom Tov, and not use any form of transportation on those holy days if possible. For those with special needs, it is permissible to use electric vehicles, if necessary to allow participation in communal prayer and meals, so long as they avoid intercity travel, expenditures (tolls, parking, charging, maintenance), and carrying goods. But in an emergency, everything is permitted to preserve life.

Based on this, Rabbi Nevins shares that he voted against the more restrictive position because “by collapsing any distinctions between types of motors, they removed the incentive to switch to the less problematic (both ritually and environmentally) class of EVs. Moreover, they declined to offer general permission to classes of individuals, such as the frail and disabled, to use an EV to reach synagogue.” He instead voted for the permissive position despite his understanding that “there remain many potential stumbling blocks when using EVs on Shabbat… and that their permission may be too broad. An opportunity to reinforce the value of localism on Shabbat may have been lost.” Thus, a pandora’s box may have been opened on the altar of preserving nuance. Rather than contribute towards the repair of Conservative communities, such decisions provide an explicit allowance to continue living far from shul, and thus far from Jewish interaction outside of shul, so long as one can afford a Tesla.

Virtual Minyanim

A far more corrosive example of this, though, can be found in the Conservative Movement’s allowance for Virtual Minyanim (both on Shabbat/Yom Tov as well as during the week). The CJLS sent out emergency guidance early in the COVID-19 pandemic and a teshuvah supporting it on Shabbat was submitted to the CJLS by Rabbi Joshua Heller in 2020. It was approved with 19 votes, including Rabbi Nevins.

Summarizing his own position for Torah and Technology, Rabbi Nevins notes that he allowed the recitation of barchu, kaddish, kedushah and the like for virtual services during the pandemic, provided that “no fewer than ten people “show their faces” by turning on the video” and unmuted themselves “for the responsive prayers that required a minyan, so that we could approximate the experience of being together in prayer.” Regarding Shabbat, Rabbi Nevins wrote that congregations should utilize passive livestreams as opposed to active Zoom:

Emergency circumstances were grounds for leniency, but when it became safe for ten or more Jews to gather in person, they became the primary congregation, and it became appropriate to minimize remote participation to passive observation.

Just as it was urgent and appropriate for Jewish communities to accommodate the needs of Jews isolated from one another in the most dangerous phases of the pandemic, it was also urgent and appropriate to reassert the primacy of in-person gathering when the danger had passed. Yes, there are substantial benefits to providing remote access even in normal times - relatives who are unable to make a journey to participate in a family celebration may at least witness the event from afar. Likewise, with congregants who are disabled or immunocompromised and unable to enter public spaces safely, virtual participation can be deeply important. Such situations aways deserve sensitive accommodations, whether the situation is a global pandemic or a very local and personal condition.

While Covid-19 was the most extensive and extended cause of social disruption in a century, we have subsequently experienced many other disruptions to physical gathering, from blizzards and floods to fires, hazardous air quality days and wars. We have learned valuable lessons about the importance of maintaining Jewish prayer communities even when we cannot cluster safely in person. And we have also learned how precious it is to gather once more when the danger has passed. With gratitude to God for ending the plague of Covid-19, we prayer for good health and joyous gatherings.

This is a beautiful statement that affirms what many no-doubt believe. However, within the Conservative Movement it sadly has little effect. Only one year after the initial emergency decision, in 2021, Rabbi Heller proposed expanding the CJLS’ allowance for fully virtual minyanim beyond the pandemic. The most extreme option within his new teshuvah, that “as long as there is a real-time video and audio link such that at least 10 adult Jews can be seen by each other and can see and hear the leader, then any rituals for which a minyan might be required may (and should) be performed” was approved by the CJLS with 9 votes. While a mutually-exclusive teshuvah by Rabbi David Fine was also approved by the CJLS with 12 votes, Rabbi Nevins himself notes in Torah and Technology that

As immunity and infections became milder and less common over the next two years, communities returned to normal public worship. Such returns were uneven, however, with some community members reluctant to return in person out of health concerns, while others had established meaningful gatherings online that they preferred to their local options. The crisis was destabilizing to synagogues, some of which flourished as never before, while others struggled or failed.

Combined with the fact that, during the pandemic, “many congregations that had resisted live streaming their services on these holy days made emergency accommodations and relatively few have discontinued them” many more Conservative synagogues were hurt than helped in the realm of in-person attendance. The unfortunate fact of the matter is that a growing number of synagogues have found themselves paying the price for this cat being let out of the bag at all.

Rabbi Nevins, of course, cannot possibly be blamed for the direction Conservative Judaism has headed in. To the contrary, Torah and Technology proves beyond any doubt that he is doing everything in his power to fight against corrosive trends within the movement. It is important, however, to note the dangers that come from decisions that do not take how laypeople will act on the ground into sufficient account. Few stomach nuance well and even fewer read or follow CJLS teshuvot. All they hear, and might or might not act on, are the resulting headlines.

Nonetheless, there is much for Orthodox readers to learn from Rabbi Nevins. The amount of care and research that went into teach teshuvah in the volume is breathtaking. His sensitivity to broader concerns (be they protecting human dignity, the dignity of the environment, or the dignity of his thoughtful readers) and his commitment to Halakhah as a Divine path towards a holier life is evident. One cannot help but be reassured that someone with his scholarship, erudition, and integrity has had such an impact on the next generation. Commitment to nuance may be a weakness in public policy, but it is invaluable in developing thoughtful leaders.

Rabbi Nevins concludes Torah and Technology with a discussion of various ideas within the Jewish understanding of mourning. In doing so, he writes as follows:

To be comforted among those who mourn for Zion and Jerusalem is to expand one’s consciousness beyond the bounds of the current painful moment. Reality is not only what we see and experience today. Reality includes the past and future. Our loved ones may seem out of reach, but if equipped with the proper perspective, we may yet feel their continued power of anchoring our past and guiding us toward a better future.

In that living a halakhic life, too, is about allowing the past to lead us into a brighter future, there are no better words to end on.

A beautiful book for the five people in the conservative movement who care. The halakhic decisions of the Conservative movement are about as relevant as the decisions of the Esperanto language committee and both.for the same reason.

A far better lesson to learn imo, is why.